Educational funding may not be going where it’s supposed to, auditor general says

Ontario’s auditor general, Bonnie Lysyk, released the 2017 audit report Wednesday afternoon.

BELLEVILLE – The Ontario Ministry of Education can’t confirm that funding for special education is being spent on its intended purpose, according to the auditor general of Ontario’s report released Wednesday afternoon.

The extensive report focuses on how effective school boards are in Ontario and whether the province’s education system produces the desired outcomes.

In the 2016-17 school year, Ontario school boards received $22.9 billion in funding from the ministry and municipalities that went toward grants for student needs. Around 30 per cent of that funding came from education property tax – taxes collected by municipalities from property owners and given to the local school boards – while the remaining 70 per cent came from the ministry.

Locally, the Hastings Prince Edward District School Board received $185 million for the 2016-17 school budget and $192 million for the current school year, according to Kerry Donnell, the board’s communications officer. “School boards are funded on a per-student basis,” she explained.

“It’s based on enrolment. Essentially there’s a funding formula by the Ministry of Education and they factor in the number of students times various components of the funding factor, and that is what determines the school boards’ budgets.”

The report by Auditor General Bonnie Lysyk says that across the province, grants for special-education purposes are not always given in accordance with the number of students in the program. If the ministry gave special-education funding based on the number of students receiving special education, $111 million would have been distributed differently across the province’s boards, it says.

Based on this, 39 boards would have received on average $2.9 million more in funding, while 33 boards would have received $3.4 million less.

Lysyk’s report also says that the ministry doesn’t know if additional funding given to school boards because of their areas’ socio-economic conditions, geographic location or cost of teachers’ salaries is actually going toward its intended purpose.

Her report also raises concern about a rise in the number of sick days being taken by school-board employees. Over the five-year period ending in 2016, there was an increase of 29 per cent in the number of sick days taken, it says.

Scott Marshall, president of District 29 (Hastings-Prince Edward) of the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation, said that being a teacher is a very stressful job and often teachers come to work even when they’re sick.

“If you look at the statistics, you see that the number of stress-related diseases in the profession are much higher then elsewhere,” said Marshall. “There are statistics supporting an increase of violence in the classrooms today. It’s concerning that the number of illnesses are where they are at, but I would often say teachers come in when they are ill too. They are very dedicated to being there.”

The report recommends that the ministry ensure school boards develop effective attendance-support programs.

That recommendation was one of 15 in the section of the report dedicated to school boards’ management of financial and human resources.

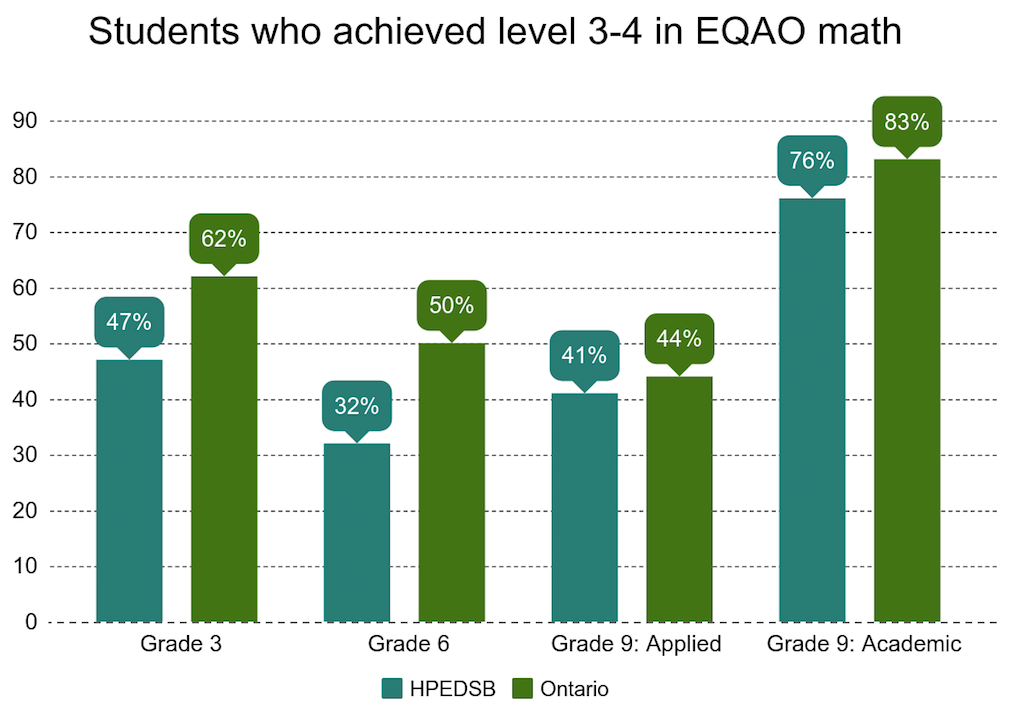

Lysyk reports that math scores in the province remain under the provincial standard and suggests the ministry develop a plan of action to improve students’ math skills. Students in the local public board have consistently remained below the average in Grades 3, 6 and 9 in provincial testing carried out by the Education Quality and Accountability Office.

But Marshall said the provincewide testing is limited in determining student achievement: “All the concerns about what standardized testing does are playing out as we see the EQAO in all the schools.”

The final recommendation by the auditor general is that the Ministry of Education make sure taxpayer dollars given to school boards are used for their intended purpose.

With files by Katie Perry, QNet News.

Print This Post

Print This Post