50 years later, he’s still got questions about the Kennedy assassination

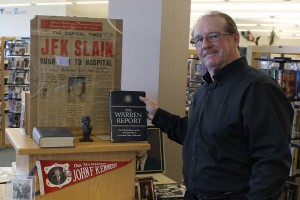

Duncan Armstrong set up a display of his research on the assassination of former U.S. president John F. Kennedy. Armstrong held a discussion and display at Quinte West Public Library on Nov. 18.

By April Lawrence

QUINTE WEST – On Nov. 22, 1963, former U.S. president John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. Fifty years later, there is still speculation surrounding the events of that day.

Retired Trenton High School physical-education teacher Duncan Armstrong has been researching the assassination for 36 years. His interest began before Kennedy was elected president.

“When Kennedy came on the scene, it was big news,” said Armstrong. “He was an ex-military hero, the youngest president, Catholic and glamorous.”

Kennedy caught the attention of youth, said Armstrong. It was not just teens and young adults but even seven- and eight-year-olds like himself.

Growing up in a military family, he was up-to-date on national and international news and politics even as a young child.

Armstrong watched as Kennedy was elected leader of the Democratic Party and later president. He said he remembers watching the Kennedy-Nixon debate, the first time election debates had been broadcast on television.

A lot happened during that era. The space race was on and Martin Luther King Jr. made his famous “I have a dream” speech. King’s speech was another milestone televised event that continued to intrigue Armstrong: “Things are changing, things are different, and it all sort of came back to Kennedy,” he said.

He was at school when he heard about Kennedy’s assassination. Right off the bat people were leaning toward a Communist conspiracy group being to blame.

“My first reaction when I heard about it, I was just getting on a bus,” he said. “It had already happened and we were in school. It was like my breath was taken away, and all I could think of was nuclear war.”

Everyone was glued to the television for days following the assassination, he said. He compared it to more recent events like the O.J. Simpson trial and 9/11. Television, newspapers and magazines covered nothing but the shooting for four days.

Hours after the assassination Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as the 36th president of the U.S. This was crushing for Armstrong, because to him Johnson represented an image that Kennedy had changed.

“I think that’s where the sense of … loss of direction was going to take place,” he said. “Not to say Johnson didn’t do some good stuff – he did.”

The report of the Warren Commission, the official investigation into the assassination, was published in 1964. The report takes up 26 volumes; approximately 3,000 sets were produced. So not many people got to read the full report, Armstrong said.

“You just had to sort of blind faith believe, ‘Well, okay, that’s what they say, that’s what happened. Who am I to question?’ ”

For a while people were distracted by the events of the tumultuous 1960s, like the Beatles and the hippie movement, but then in 1968 King was shot, followed by the assassination of Kennedy’s brother Robert.

“When Martin Luther King got shot everybody stopped. When Bobby Kennedy got shot, everyone was like, ‘Something’s not right here.’ And that’s when you went back to the (John) Kennedy assassination and said, ‘Wait a second here – what’s going on here?’ Not too long after, (with) Watergate, trust in the government was out the window,” said Armstrong.

He began researching the assassination as the topic for a paper he wrote in 1977 as a University of Ottawa student.

Armstrong said he has seen how sensationalized things get with the subject and so tries to look at it more seriously. It isn’t his goal to tell people what he thinks happened, but to use his research to start people thinking about it and encourage them to draw their own conclusions, he said. He tries to focus on why it happened, not how it happened.

Some findings from Armstrong’s research:

The 1968 book The Day Kennedy Was Shot, by Jim Bishop, largely followed the findings of the Warren Commission. “The famous point of the book is when Kennedy is shot,” Armstrong says. “That’s when you think (Bishop) should have all his facts in a row. And he says John Connally, who was the (Texas) governor who was sitting in front of Kennedy, he said that when the shots rang out Connally’s big Texan hat fell off his head. Which isn’t what happened: Connally was holding his hat in his hand at the time of the shooting. If this guy is so wrong about that most important time, what else is wrong?”

According to Armstrong, Marina Oswald, the wife of assassin Lee Harvey Oswald, testified to the Warren Commission that the morning of the shooting he had left his wedding ring where she was living at the time. In Russia, where she was from, doing that symbolized Oswald saying that the marriage was over. But Armstrong has found in a famous photo of Oswald that he is still wearing his wedding ring. He can tell it is the wedding ring because the same ring is in other photos, including one where Oswald is holding a gun.

Re-enactments of what happened conducted by investigators have also raised questions, Armstrong says. “In the re-enactment they used the followup car. They were different heights. Why didn’t they use the real limousine? The other thing about the limousine: it was taken away, stripped down to nothing and put back together.”

The route Kennedy’s motorcade took that day was changed; it was originally going to be a straighter route. When the route was changed it was kept secret and wasn’t supposed to be released, Armstrong says. That route took the president directly toward the Texas School Book Depository, the building where Oswald was positioned. Armstrong says that raises the question of why Oswald didn’t shoot sooner when he had a direct easy shot. Also, as the motorcade was starting, a radio broadcast announced the new route, which was supposedly still top secret. This raises the question of how the broadcaster knew the new route.

Print This Post

Print This Post