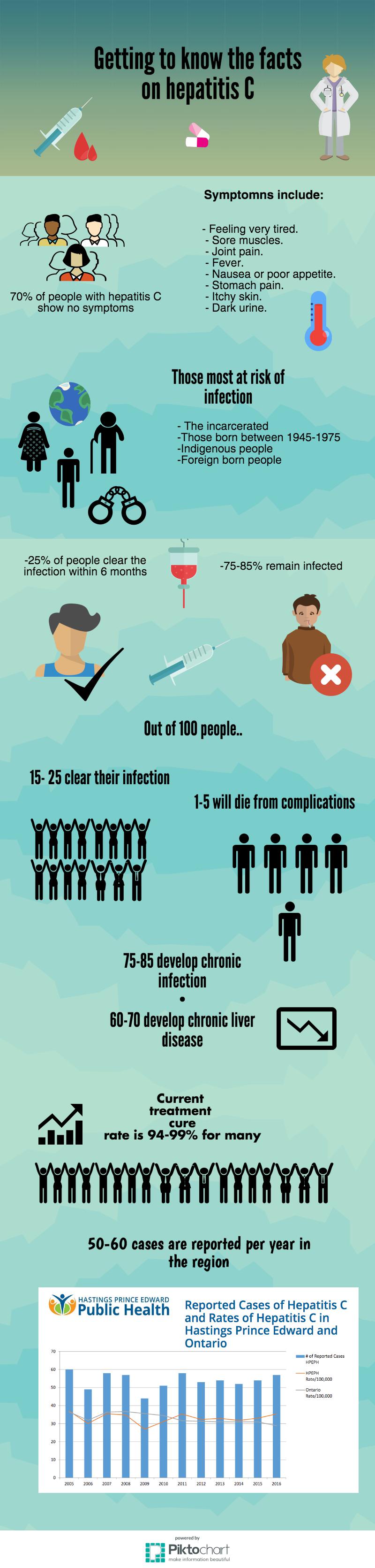

Getting to know the facts surrounding hepatitis C

The Hastings and Prince Edward Counties Health Unit say they receive anywhere from 50 to 60 cases of hepatitis C per year. Photo by Makala Chapman, QNet News.

BELLEVILLE – More than 70 per cent of people infected with the hepatitis C virus don’t even know they have it say local health officials.

If left untreated, Hepatitis C, a blood-borne infection, can lead to serious liver damage and death.

The illness is most commonly known for being spread through the exchange of used needles and through contact with contaminated blood.

Stephanie McFaul, the program manager in health protection at Hastings and Prince Edward Counties Health Unit, says the cure for the hepatitis C virus is up to 95 per cent successful. Photo by Makala Chapman, QNet News

Stephanie McFaul, the program manager in health protection at Hastings and Prince Edward Counties Health Unit, says that curing the virus is much easier than it used to be prior to the turn of the century.

“I think that treatment has really evolved,” she said. “The treatments were much less effective even a few years ago.”

Taylor De Grace, a 20-year-old radio broadcast student at Loyalist College, says that while he doesn’t know anyone with hepatitis C, he knows it’s an illness that could impact his parent’s generation.

“It is often the cause of various types of cancers in (older growing) populations which are people that very soon our generation will have to take care of,” he said.

De Grace also said he felt it was ultimately a shared responsibility for everyone to learn about the virus.

“It’s important to have hepatitis C in public consciousness so we can have more conversations about it and how we can prevent it,” he said.

While anyone could contract the virus, the health unit said that those most at risk include people who were born between 1945-1975, those in prison, the indigenous population and foreign-born people.

McFaul said improved laws and medical practices in Canada since the 1970’s have helped decrease the spread of the virus.

Still out of 100 people that contract hepatitis C, up to five will die from complications caused by the sickness.

But there’s good news for those living with the chronic illness.

“For many individuals, 95 per cent of people actually, (they will) have a successful treatment and are therefore effectively cured from hepatitis C, which is incredible,” McFaul said.

While she also noted that there are still 50 to 60 cases reported to the health unit throughout the year in the region, she said those numbers are on par with the provincial statistics.

“People need to be aware of their potential risk factors and get tested,” she said, while adding that the initial screening test isn’t always perfect.

But for McFaul, she said the best way to tackle the virus, like many other illnesses, is to spread awareness and practice prevention.

“If people are aware that they are infected and can therefore follow up and receive appropriate treatment, then we are reducing the reservoir for potential transmission in the future,” she said.

But in order to receive the costly treatment, which consists of an oral tablet, there are certain criteria that must be met.

“One has to almost wait until they have progressed along that disease spectrum so that their liver is already quite diseased and damaged before they are even eligible to receive treatment,” said McFaul.

In the past, doctors had to be selective about who they would bring on to treatment because it was a costly procedure and it wasn’t always guaranteed to be successful.

Lobbyists have since gone to get the government within the last year to ask them to look at loosening the requirements surrounding treatment eligibility.

“The policy makers need to evolve along with the science and sometimes that just takes time,” said McFaul.

Source: Hastings And Prince Edward Counties Health Unit. (Stephanie McFaul, program manager at the health unit).

Print This Post

Print This Post